SUNDAY, 11 FEBRUARY 2018

With approximately 160,000 described species, and having evolved over 260 million years ago, Diptera are amongst the most diverse groups of organisms on the planet. They also mean a lot of science, and vinegar flies have been directly involved in Nobel prize winning work for physiology or medicine six times. The University of Cambridge has the capacity to grow millions of vinegar flies at any time.Flies are found on every continent on Earth; the collection at the Natural History Museum (NHM) in London contains the fruit of expeditions to every conceivable environment: from the Central Asian stepp, to the lush jungles of South America, to the summit of Everest and the deserts of Africa.

Matt Brady interviewed Dr Erica McAlister, author of the recent book The Secret Life of Flies, and Senior Curator of Diptera and Siphonaptera at the NHM, to talk about her work, her numerous projects in far flung corners of the planet, and the future of human consumption as we know it.

MB: Dr McAlister, what’s the most challenging field environment you’ve experienced in your career?

By Martha Dillon

By Martha DillonMB: To what ends have you gone to collect a sample?

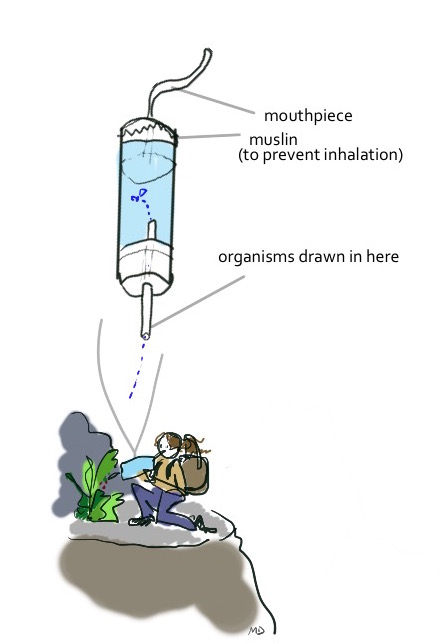

EM: The most extreme environment I’ve worked in was when I had to hoover flies off a mountainside 5000m up, from a potato which is growing in the side of a cliff. You’re constantly reminded of the hierarchy of ‘specimen first, equipment second, and everyone else third’; I always remind my students that I can get more of them, but not more of my samples.

MB: Have you ever put your body on the line for the sake of science?

EM: Personally, no, but on an expedition in a rainforest a friend of mine had a Bot Fly larva burrow into his head, where he kept it for a week, after which he insisted I take it out. Apparently, he could feel it moving at night, and because the larvae defecate, it had started to ooze. It’s really hard to find Human Bot Flies like that, so it’s wriggled its way into the collection.

MB: When you aren’t scaling cliffs, or fighting off nests of Redback spiders in the Australian outback, you spend a lot of time in the NHM, in London. While the environments are clearly different, are there skills that overlap between the two?

EM: You have to make sure you keep really good notes about everything. I have so many issues where other people have collected data for me, and they cause me an absolute headache when they scrawl something down incorrectly. You have to calm yourself down from the excitement of collection and then investigation in the lab, in order to get all of the data. We don’t like killing things, but it’s necessary for the collection, and if the data isn’t there or is wrong, you’re like ARRRRRGH!

MB: Note-taking must have been been paramount when the NHM’s vast collection - containing over 2.5 million specimens of flies comprising approximately 30,000 species - was re-examined. How are these used by the museum?

By Molly Cranston

By Molly CranstonMB: Your book highlights the crucial importance flies could play in feeding ourselves and our livestock in the future. Can you see everyone eating flies or maggots?

EM: Environmentally, eating maggots (the immature stage of the fly) is brilliant because you’ve got no methane production, the water requirement is minimal, there are no by-products, and you’re not causing oceanic species loss. When it comes to us eating insects, two-thirds of countries in the world already consume insects in some way, for us, it’s just a case of getting over our weird qualms about eating them – we drink cow’s milk for goodness sake! They are so rich in protein but perhaps protein-rich flour [from maggots] is the way forward. I’ve eaten lots of maggots and insects, and I’m especially a fan of Anty Gin from the Cambridge Gin Distillery.

MB: It seems like you’ve been everywhere, where next?

EM: I want to go to Mongolia, first, and then to New Zealand to see a bat fly where it’s the only species, in its own genus and family. They live in colonies, surviving on bat poo. What’s so amazing is that there is communal living with males and females cleaning each other, which is essentially a unique trait in the fly world. The thing is when writing the book, every time I wrote or heard about a new habitat it triggered this feeling that I have to go and see it.

Clearly, Dr McAlister’s tenure at the museum has not made her lose her sense of adventure. Her desire to explore some of the world’s most challenging terrains in search of one of the physically smallest, yet most diverse groups of organisms on the planet is palpable. This is evident when you hear her talk on podcasts such as No Such Thing As A Fish and Do The Right Thing, in her book The Secret Life Of Flies, or in one of her numerous public engagement events at the NHM. It is truly refreshing to hear someone so passionate, honest and funny spread the word about science, its pitfalls, but also its huge capacity to be exciting and different – her style is something on which others in science communication should take note

Dr Erica McAlister’s book The Secret Life of Flies was published by the Natural History Museum in 2016.

Matthew Brady is a PhD student in the Department of Earth Sciences at Darwin College. Artwork by Martha Dillon and Molly Cranston. Banner Image by Johan J.Ingles-Le Nobel