WEDNESDAY, 18 JANUARY 2012

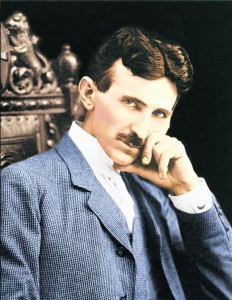

Most of us know the name Thomas Edison, the prolific American inventor who produced the first practical electric light bulb. Why then, do relatively few know of Nikola Tesla, Edison’s Serbian-American arch-nemesis, and the years-long, bitter rivalry between the two—one which may have ultimately cost them both the Nobel Prize?Tesla was born in 1856, an ethnic Serb in what is now part of Croatia. While his mother invented gadgets for use around the house, including a mechanical eggbeater, his father was an Orthodox priest who was adamant his son was to follow in his footsteps and enter the priesthood. The young Tesla was already showing early signs of brilliance, including baffling his teachers by performing integral calculus in his head, and was equally adamant that he would study engineering at the renowned Austrian Polytechnic School. He would later describe the feeling of being “constantly oppressed” by his father’s ambitions. Clearly, someone would have to give in, and that turned out to be the older Tesla: when Nikola contracted cholera at age seventeen and his life hung in the balance, his father promised that if he survived, he would get his wish and attend the Austrian Polytechnic.

Despite this hard-won struggle to be allowed to attend, Tesla did not receive a degree from the university, leaving in his third year. In 1878, the year he left, he broke off contact with friends and family and moved to Marburg in Slovenia, leaving friends believing he had drowned in the Mur River. At this point he suffered a nervous breakdown, and there would be further indications throughout his life that not all was well within that rather extraordinary mind—he is now believed to have suffered from obsessive-compulsive disorder (OCD). For the next four years, he worked for various electrical companies in Budapest, Strasbourg and Paris.

It was in Budapest, working for the Central Telephone Exchange, that he conceived the idea of the alternating current (AC) induction motor. He would later claim that this invention came to him fully formed as he walked in the park: “In an instant the truth was revealed. I drew with a stick in the sand the diagram shown six years later [when he presented his idea to the American Institute of Electrical Engineers].” However, no one in Europe could be persuaded to invest in such an outlandish idea, given that at the time the world ran on direct current (DC). Tesla decided he had to go to America to work with Thomas Edison, the great electrical engineer who had a near-monopoly on New York City’s electrical power. Arriving in the USA with nothing but four cents in his pocket and a letter of introduction from Edison’s business associate Charles Batchelor, he was duly hired.

However, Edison, wary of losing his DC-based electrical empire, tasked Tesla only with improving his DC power plant, and would not fund any work into AC. After a few months, Tesla announced his work on the power station was finished, and asked for the $50,000 payment Edison had promised him—only for the American to claim the offer had been a joke.

Losing no time in walking out of Edison’s company, Tesla dug ditches to pay his way until A.K. Brown, of the Western Union Company, agreed to invest in the AC motor. From his New York laboratory, surrounded by power cables and electric trams running on Edison’s DC, Tesla put together the pieces he had seen in that moment of clarity in Budapest. From out of his mind came the first AC motors, now tangible, material and “exactly as I imagined them”. This was the starting point for an electrical revolution.

What came next would change the world. In the winter of 1887 Tesla filed seven US patents relating to polyphase AC motors and power transmission. Put together they were the blueprints for a complete system of generators, transformers, transmission lines, motors and lighting that would prove to be the most valuable US patents since Alexander Graham Bell’s telephone. Polyphase power is the system of power transmission now used across the world; AC current enables the use of the transformer effect, essential for the high-voltage power needed for economically viable long-distance transmission.

The scope of these innovations was not lost on the industrialist George Westinghouse, who saw that Tesla had made the missing link in the challenge of transmitting power over long distances. Westinghouse bought the seven patents that would change the world for $60,000, and a $2.50 royalty for Tesla per horsepower of electrical capacity the Westinghouse Corporation sold. The next challenge would be how to sell AC to anyone in the face of Thomas Edison’s high-powered propaganda war against this rival technology.

The resulting smear campaign was the ugliest facet of the ‘War of Currents’. Edison’s desire to protect his technology and denounce AC as dangerous drove him to publically electrocute dogs, horses and an elephant with AC. In addition, he funded the invention of the first electric chair—powered, naturally, with AC.

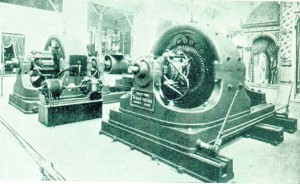

Power supply is a pragmatic business however, and the Westinghouse Corporation’s AC system was undeniably more efficient and practical than DC. In 1983 Chicago hosted the Columbian Exposition, the first ever all-electric fair. Westinghouse won the bid to illuminate it, and AC so outclassed the DC technology that Tesla and Westinghouse’s expenses were half that of Edison’s failed bid. At the fair, a hundred thousand incandescent lights lit the buildings, including the Great Hall of Electricity, where the polyphase system was displayed to 27 million visitors. From then on over 80 per cent of the electrical devices ordered in the United States ran on Tesla’s system.

The ‘War of Currents’ might have been over, but it would have lasting consequences. Both Edison and Tesla were nominated for Nobel Prizes in Physics, but neither won, and it has been suggested that their great animosity to each other and refusal to consider sharing the Prize, led the Nobel Committee to award it to neither of them.

The rest of Tesla’s life might not match the high scientific drama of his rivalry with Edison, but he remained an active and productive mind. As he had in Budapest, he would develop his inventions mentally, seeing them fully-formed and in perfect detail, then simply recreate them in reality. Some ideas came to fruition; at his death Tesla held hundreds of patents, the last one filed at the age of 72. Some were ahead of their time, and some were simply bizarre. His concept of using radio-waves to detect the presence of ships, more than 20 years before the invention of radar, sits alongside his unfeasible claim to have invented a particle beam that could bring down aircraft from 250 miles; prime examples of both great prescience and extreme eccentricity.

When Tesla died in 1943, over 2000 people attended his state funeral in New York. His impact is possibly best expressed in the words of the then Vice President of the Institute of Electrical Engineers: “Were we to seize and eliminate from our industrial world the result of Mr. Tesla’s work, the wheels of industry would cease to turn, our electric cars and trains would stop, our towns would be dark and our mills would be idle and dead. His name marks an epoch in the advance of electrical science.”

Sarah Amis is a 2nd year undergraduate studying biological Natural Sciences