SUNDAY, 11 FEBRUARY 2018

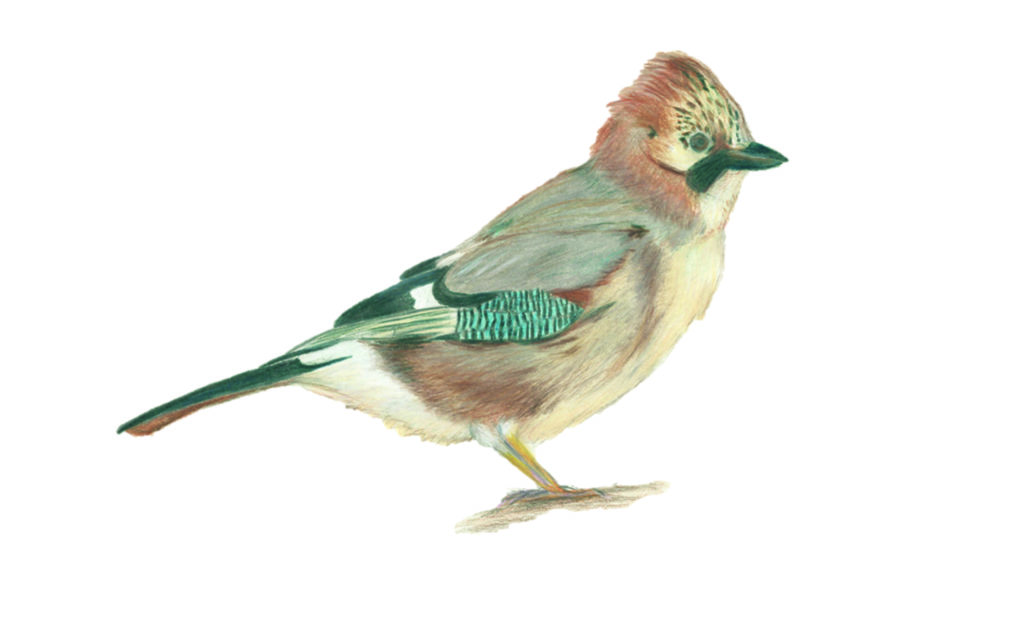

If you walk into the kitchen and see your friend jumping around holding onto their foot, you are likely to think that they have stood on something painful, not that they are performing a ritual rain dance. Humans have the ability to decode the thoughts, beliefs and emotions of others, allowing you to predict and understand peoples’ actions because we are able to hypothesise others’ thought processes. This ability to place ourselves in the position of others is an insight developed over millions of years of social and biological evolution. However, there is growing evidence that non-human animals may have similar ‘mindreading’ abilities.Members of the corvid family, including crows, rooks, ravens, jackdaws, magpies and jays, have a well-deserved reputation for being one of the most intelligent groups of animals, perhaps even on an equal footing with great apes and dolphins. Their skills range from intricate tool use to complex social interactions and extensive memory skills. Corvids are known for their food-caching strategies, burying seeds when they are abundant and recovering them in times of scarcity. These birds remember what, where and when they cached in potentially hundreds or thousands of locations.

Ravens, California scrub jays and Eurasian jays all employ cache protection strategies to keep their cache locations disguised from potential pilferers. When a competitor is eyeing them up, scrub jays will choose to cache in shaded or out-of-view places to avoid their gaze. If the competitor is within earshot they will also choose quieter substrates to hide their food in. Scrub jays that are watched by a competitor while caching will often come back to hide the food somewhere else once the competitor is gone. However, cachers only do this if they have previous experience of being a thief and pilfering the food cached by others. Birds that have never been thieves do not re-cache after they have been watched. These findings suggest that caching birds may be able to perform a mindreading trick known as experience projection. The cacher uses their own experience to outwit the pilferer by imagining the other bird’s point of view and mentally placing themself in the thief’s position. In the opinion of Dr Ed Legg:

“this is probably the best evidence that a non-human animal can predict another’s action by ‘putting itself in the shoes’ of that other individual.”

Eurasian Jays have been observed to lie atop of anthills with their wings splayed out, allowing themselves to be sprayed with formic acid from its resident ant colony. They likely do this in order to prevent parasites colonising their plumage

Eurasian Jays have been observed to lie atop of anthills with their wings splayed out, allowing themselves to be sprayed with formic acid from its resident ant colony. They likely do this in order to prevent parasites colonising their plumageThe best way to test whether males are tuned to their partner’s desires is to alter the female’s desire for different foods and see whether the male responds. In experimental conditions the desires of female jays can be manipulated using specific satiety. This sensory phenomenon occurs when you eat a lot of one type of food, resulting in that food seeming less appealing. For example, after dinner you may be full of pasta but happy to eat a dessert! If a male jay sees his partner eat a whole bowl of mealworms, he should predict that her desire for more mealworms is reduced and she might prefer waxworms instead. Considering the situation from the female’s point of view allows the male to respond to her desires – a skill known as perspective-taking.

Ljerka Ostojić with Caracas, one of the jays she works with at the Cambridge Cognition Lab

Ljerka Ostojić with Caracas, one of the jays she works with at the Cambridge Cognition LabHowever, understanding what others want is not always that simple; even humans struggle to disentangle their own desires from those of others. As we grow older (most) humans become better at this, but younger children will egocentrically select what they desire most. In a well-known study by psychologists Repacholi and Gopnik, one-year-old children watched adults making obvious “Eww!” and “Mmm” sounds indicating that they enjoyed raw broccoli rather than goldfish crackers. Despite these cues, the infants preferred to offer crackers to the adults no matter how emphatically the adult showed that they did not like them.

In a close comparison to this, the desires of male jays interfere with their ability to respond to the females’ desires. When the male jay is also pre-fed to satiety on one type of worms he will nearly always offer the female the worms he currently prefers. However, crucially, when the female is pre-fed on the opposite worms, he will still give her some of the worms that she desires even though he does not want them himself. This suggests that the male’s sharing choices are influenced by a combination of his own desires and the desires of the female. This matching finding in jays and humans suggests that birds may use their own experience of internal states to judge others’ states in a way similar to humans. In Ljerka Ostojić’s opinion:

“testing what the birds cannot do is just as important as testing what they can do. Investigating limitations of their cognitive processes might bring us closer to understanding the nature of these processes.”

Research into the advanced cognition of corvids is ongoing, but as we learn more about what other animals can and can’t do we are better able to understand the mechanisms behind our own cognitive abilities. As the evidence grows that social interactions of humans and birds may be based on similar underlying rules, it could well be time to retire the pedestal on which we have placed human social intelligence.

Rachel Crosby is a PhD student in the Department of Psychology

Image credit: Sandy Sarsfield